|

| Jacob Tonson, founder of the Kit-Cat Club, portrait by Godfrey Kneller, 1717. |

It would be hard for Christopher 'Kit' Cat ( or Catling') to imagine that his pies and more importantly, his tavern, The Cat and Fiddle, would be the origin of one of the most prominent literary organisations from the 1690s to the early eighteenth century, The Kit-Cat Club.

Over feasts of mutton pies and cheesecake and other baked goods, in The Cat and the Fiddle, that the bookseller and publisher, Jacob Tonson, created the Kit-Cat Club. The Kit-Cat Club was believed to be either named after the baker or the pie itself, which was called a 'Kit Kat.' [1]. The club started up as a publishing rights deal by Tonson, who would establish professional friendships in a weekly meeting over baked goods, in the return that 'The bookseller's friends would give him the refusal of their juvenile productions.' [2] It was by feeding these members of his club, that Tonson hoped to obtain the loyalties by their stomachs and in the hopes for long-term profits. The Kit-Cat Club was not the first of its kind, and could actually be regarded as an extension of the coffee house, which had the reputation as the 'penny university,' in the early modern period. The Kit-Cat Club different itself though due to the fact that had multiple interests and it had political, cultural, and professional purposes, compared to other organisations such as trades guilds, which tended to have one purpose. [3].

The members of the Kit-Cat Club were Whigs politically, and they were wanting to challenge the preconceived notions of being a Whig. In the Civil War and the Restoration periods in British history, Whig clubs had the reputation of being a hot-spot for treachery and were against the monarchy. The Kit-Cat club tried to distinguish itself from this pre-conceived notion and would try and make gentlemen's clubs fashionable for Whig Gentlemen with an emphasis on literature and culture. [4]. This emphasis on creativity and culture on the club was a major attraction for the 50 members of the club, especially as writing for money was condemned by Renaissance critical theory, which had limitations on the authors imaginative freedom, and that writing in the seventeenth century was often for the wealthy and those who had private income.

The Kit-Cat Club was created in a great change of public opinion when it came to literature and creativity. In 1695, there was the lapse of England's Licensing act, which saw the surge in the number of printed materials, such as books, papers and pamphlets getting printed, especially political material. This led to more creative freedom and allowed anyone to get published, not just the aristocracy. This increased freedom still left the possibility of printers and authors being arrested under obscenity and blasphemy laws, such as pro-Jacobite material. Despite this, it led to around 21,000 books getting published in Britain in the 1710s. [5]

The Kit-Cat Club was best known for its desire to be involved in high-brow culture and also in creativity. Many of the members of the Club were music, opera, and theatre aficionados. One of the members, Joesph Addison, produced the opera of Rosamond along with his play that he wrote, Cato, a tragedy, and The Spectator magazine. [6] The building of the new Haymarket Theatre was designed by member Vanbrugh. Club members would eventually hold ten exclusive music recitals between November 1703 and March 1704, in the Drury Lane and the Lincoln's Inn Theatres. [7 ]

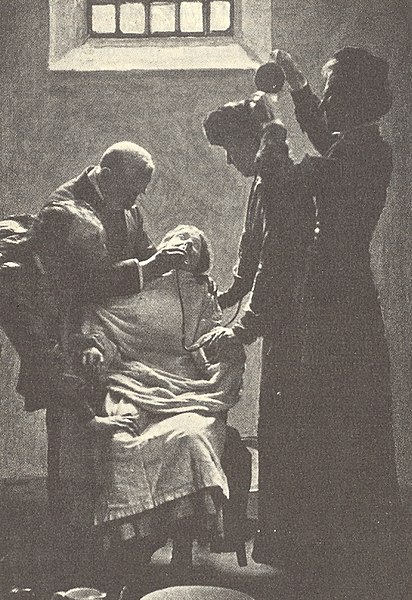

|

| Issac Bitterstaff, the 'author,' of The Tatler and Spectators, but was in fact, the pen name of Sir Richard Steele, from the frontt cover of the 1759 Tatler cover. |

|

| Godfrey Kneller, Joseph Addison (1672-1719), and Sir Richard Steele (1672-1729), |

The club focused on Wiggish politics of the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries, there were many leaders of the Whig political party who were members. Some of the members of the club were political figures, such as Sir Robert Warpole, who would later become Prime Minister and The Earl of Stanhope, and Thomas Wharton, who would eventually become the Lord Luitenant of Ireland. [10] in The Club also believed in the whig policies of a limited monarchy with a strong parliament, resistance to the French aggression, the union of Scotland and England, and most importantly, the support of the House of Hanover. [8] The Kit-Cats were involved in politics in the reign of Queen Anne, due to the Whigs being against the government. In 1703, it was believed that Tonson was involved in a political mission when he went to Holand. Kit-Cat meetings were believed to have been held and had considered parliamentary action to remove Abigail Masham, one of Queen Anne's favourites from her service. In the final illness of Queen Anne in June 1914, meetings were held every night. [9] In November 1713, Tonson was in Paris, investigating a Jacobite plot. [11]

The Kit-Cat's attempted to stage a public demonstration against the Tories on 17 November 1911. They had managed to get at least one thousand pounds from subscribers. They made effigies of the Pope, Devil, various Jesuits and religious figures, and they were to be burned. They had apparently distributed money for a riot to take place with this demonstration. The Kit-Cat Club's activities were thwarted by Tory ministers who took the effigies and held them until the riot was over. [12]

The Kit-Cat Club was believed to have been ended by 1720, and it was believed that it was Tonson which was the force which kept the Club in full swing. It is believed that it was Tonson's absence in Paris from 1718-1720, which brought the club to the end. [13] The once so very influential club which had its fingers in political and creative pies has almost been forgotten, and there has been shockingly little written about this club, especially as they helped to shape England politically, creativity, and more importantly, influenced social and political behaviour of the public through their publications.

Despite the influence of the members of the Kit- Cat Club, there has been little written about them, one of the prominent pieces of literature is by Ophelia Field, which has been the foundation of this study. The Kit-Cat- Club is best remembered not for their publications or their political activity, however for their toasting. The tradition of toasting for the club was part of their dinner ritual which was initiated by Tonson once he signalled that the meal was over. The toast would be given to the 'beauties,' among the ladies of the town, who would have to be Whig and beautiful, one these toasties would be Lady Mary Wortley Montegue. This would involve balloting the women to pick which one was toasted and the woman who was nominated would have her name engraved on a drinking glass. However, there are no surviving 'Kit-Cat glasses' with the names of women. [14]

|

| A. Gow, The Introduction of Lady Mary Wortley Montague to the Kit Kat Club, 1873 |

Despite the influence of the Kit-Cat Club and its members who would have careers in literature, politics and other pursuits, it is difficult to name them and their activities have been forgotten. The 42 'Kit-Cat Club', portraits by Sir Godfrey Kneller which are held in the National Portrait Gallery, London, show the members of this once influential society. Unfortunately, there is not a portrait of Christopher Cat, the Baker, who arguably started it all, and who inspired the name of this organisation. Very few bakers are remembered in history and it is not often that mutton pies help to establish a prominent London Club, but Christopher Cat and his pies managed to do both.

[1] C.J. Barrett, The History of the Barn Elms and the Kit Cat Club, now the Ranelagh Club, (London, 1889), pp. 37-38.

[2] Ophelia Field, The Kit-Cat Club (London, 2009), pp. 32-33: J. Caulfeild, Memoirs of the Celebrated Persons Composing the Kit-Cat Club: With a Prefatory Account of the Origin of the Association (London, 1889) pp. 240-241.

[3] Field, , p. 32

[4] ibid, p.34.

[5] Caufield, Memoirs of the Celebrated Persons Composing of the Kit-Cat Club, (London, 1889), pp. 132-146, 112-116, 70-84.

[6] ibid., pp.184-204.

[7] Field, The Kit-Cat Club (London, 2009), pp.132-135

[8] Anonymous, A Kit-Kat C-b described. Being a satirical character of a member of the Kit-Cat Club, (London, 1705).

[9] Field, The Kit-Cat Club (London, 2009), pp.248-257.

[10]Caufield, Memoirs of the Celebrated Persons Composing of the Kit-Cat Club, (London, 1889), pp. 34-41.

[11]ibid, pp. 182-204.

[9] K. M. Lynch, Jacob Tonson, Kit-Kat Publisher, (Knoxville, 1971), p.37.

[10] ibid, pp. 58-63.

[11]ibid., p63.

[12] ibid., p.62.

[13] ibid., pp.65-66.

[14] Field, The Kit-Cat Club (London, 2009), pp. 56-58.

Some Kit-Cat Club Members publications which are easily available online, but there is a lot more that is not as accessible. The Spectator and The Tatler are the more prominent publications and volumes of them are easily found online, especially on Archive.com.

A Kit-Kat C-b described. [Being a satirical character of a member of the Kit-Cat Club], 1705.

The Spectator :

The Spectator Volume 5 https://archive.org/details/spectatorvolume04steegoog/page/n18

The Spectator Volume 6, https://archive.org/details/spectator03steegoog/page/n26.

The Spectator Volume 8, https://archive.org/details/spectator21steegoog/page/n4

The Tatler https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.175706/page/n1

Volume one of the Tatler https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13645/13645-h/13645-h.htm.

Additional material:

C. J. Barrett, The history of Barn Elms and the Kit Cat Club, now the Ranelagh Club (London, 1889). https://archive.org/details/historyofbarnelm00barr.

J. Caulfield, Memoirs of the Celebrated Persons Composing the Kit-Cat Club (Londo, 1889), https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9ThCAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA246&dq=members+of+the+kit-cat&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi0_eWLo9nmAhUDm1wKHel1D24Q6AEIMzAB#v=onepage&q=%20opera&f=false.

Sir Godfrey Knelller, The Kit-Cat Club portraits, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/set/347/The+Kit-cat+Club+portraits%3A+by+Sir+Godfrey+Kneller.